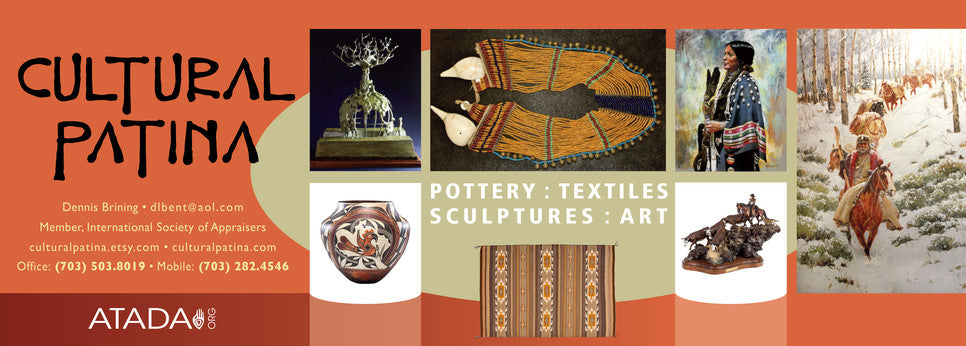

Historic Native American, Tesuque Poly Chrome Jar, Ca 1890, #1128

$ 3,620.00

Historic, Native American, Tesuque Poly chrome Jar, Ca 1890, #1128

Discription: #1128 Historic, Native American, Tesuque Poly chrome Jar, Ca 1890,

Condition: In overall excellent condition. No breaks, cracks, or chips. Surface with usual wear, including dings and abrasions. Crazing overall. No apparent restoration.

Dimensions: 8.5" x 8.5"

Some back ground on the Tesuque Pueblo"

Tesuque (/təˈsuːki/; Tewa: Tetsuge Owingeh [tèʔts’úgé ʔówîŋgè]) is a census-designated place (CDP) in Santa Fe County, New Mexico, United States. It is part of the Santa Fe, New Mexico, Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 909 at the 2000 census. The area is located near Tesuque Pueblo, a member of the Eight Northern Pueblos, and the Pueblo people are from the Tewa ethnic group of Native Americans who speak the Tewa language. The town of Tesuque is separate from the pueblo. The pueblo was listed as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[1]

Geography

Tesuque is located at 35°44′46″N 105°55′20″W (35.746069, -105.922108).[2] According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 7.0 square miles (18 km2), all land. Camel Rock is a locally-famous and distinctive rock formation and landmark, located along U.S. Routes 84/285 across from the Camel Rock Casino, which is also owned by Tesuque Pueblo.

Demographics

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 909 people, 455 households, and 249 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 130.6 people per square mile (50.4/km²). There were 541 housing units at an average density of 77.7 per square mile (30.0/km²). The racial makeup of the CDP was 75.25% White, 0.44% African American, 0.44% Native American, 0.77% Asian, 18.37% from other races, and 4.73% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 35.64% of the population.

There were 455 households out of which 16.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.5% were married couples living together, 8.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.1% were non-families. 38.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.00 and the average family size was 2.61.

In the CDP, the population was spread out with 14.7% under the age of 18, 4.7% from 18 to 24, 23.8% from 25 to 44, 41.3% from 45 to 64, and 15.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 48 years. For every 100 females there were 89.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.6 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $36,029, and the median income for a family was $80,043. Males had a median income of $43,833 versus $42,650 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $52,473. About 7.3% of families and 12.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including none of those under age 18 and 29.5% of those age 65 or over.

Notable people

Carlene Carter, singer and songwriter.

Lynne and Dennis Comeau, shoe designers.[4]

Howie Epstein, musician.

Ali MacGraw, actress and model.

Armistead Maupin, author who bought the Comeau estate.

Cormac McCarthy, author.

Anthony Michaels-Moore, opera singer.[5]

Eliot Porter, nature photographer who lived in Tesuque from 1946 until his death in 1990.

Michael Tobias, author.

Carol Jean Vigil, New Mexico's first female Native American state court judge.

Cultural references[edit]

Tesuque is mentioned in Willa Cather's 1927 novel Death Comes for the Archbishop, Book Nine Chapter 1.

There is a passing mention of Tesuque in chapter 6 of the 1932 novel Brave New World by Aldous Huxley.

Tesuque is also mentioned in the 1966 novel The Last Gentleman by Walker Percy.

Michael Tobias' 2005 novel, The Adventures of Marigold, is set in Tesuque.

In the final episode of the crime drama series Breaking Bad, the characters Elliott and Gretchen Schwartz live in a new mansion in Tesuque.

In the penultimate episode of the second season of the animated comedy drama series BoJack Horseman, BoJack visits Charlotte Moore who lives in Tesuque in a feeble attempt to rekindle an old romance with her.

Some background on Pueblo Pottery Making

“Pueblo pottery is made using a coiled technique that came into northern Arizona and New Mexico from the south, some 1500 years ago. In the four-corners region of the US, nineteen pueblos and villages have historically produced pottery. Although each of these pueblos use similar traditional methods of coiling, shaping, finishing and firing, the pottery from each is distinctive. Various clay's gathered from each pueblo’s local sources produce pottery colors that range from buff to earthy yellows, oranges, and reds, as well as black. Fired pots are sometimes left plain and other times decorated—most frequently with paint and occasionally with applique. Painted designs vary from pueblo to pueblo, yet share an ancient iconography based on abstract representations of clouds, rain, feathers, birds, plants, animals and other natural world features.

Tempering materials and paints, also from natural sources, contribute further to the distinctiveness of each pueblo’s pottery. Some paints are derived from plants, others from minerals. Before firing, potters in some pueblos apply a light colored slip to their pottery, which creates a bright background for painted designs or simply a lighter color plain ware vessel. Designs are painted on before firing, traditionally with a brush fashioned from yucca fiber.

Different combinations of paint color, clay color, and slips are characteristic of different pueblos. Among them are black on cream, black on buff, black on red, dark brown and dark red on white (as found in Zuni pottery), matte red on red, and poly chrome—a number of natural colors on one vessel (most typically associated with Hopi). Pueblo potters also produce un decorated polished black ware, black on black ware, and carved red and carved black wares.

Making pueblo pottery is a time-consuming effort that includes gathering and preparing the clay, building and shaping the coiled pot, gathering plants to make the colored dyes, constructing yucca brushes, and, often, making a clay slip. While some Pueblo artists fire in kilns, most still fire in the traditional way in an outside fire pit, covering their vessels with large potsherds and dried sheep dung. Pottery is left to bake for many hours, producing a high-fired result.

Today, Pueblo potters continue to honor this centuries-old tradition of hand-coiled pottery production, yet value the need for contemporary artistic expression as well. They continue to improve their style, methods and designs, often combining traditional and contemporary techniques to create striking new works of art.” (Source: Museum of Northern Arizona)

Discription: #1128 Historic, Native American, Tesuque Poly chrome Jar, Ca 1890,

Condition: In overall excellent condition. No breaks, cracks, or chips. Surface with usual wear, including dings and abrasions. Crazing overall. No apparent restoration.

Dimensions: 8.5" x 8.5"

Some back ground on the Tesuque Pueblo"

Tesuque (/təˈsuːki/; Tewa: Tetsuge Owingeh [tèʔts’úgé ʔówîŋgè]) is a census-designated place (CDP) in Santa Fe County, New Mexico, United States. It is part of the Santa Fe, New Mexico, Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 909 at the 2000 census. The area is located near Tesuque Pueblo, a member of the Eight Northern Pueblos, and the Pueblo people are from the Tewa ethnic group of Native Americans who speak the Tewa language. The town of Tesuque is separate from the pueblo. The pueblo was listed as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[1]

Geography

Tesuque is located at 35°44′46″N 105°55′20″W (35.746069, -105.922108).[2] According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 7.0 square miles (18 km2), all land. Camel Rock is a locally-famous and distinctive rock formation and landmark, located along U.S. Routes 84/285 across from the Camel Rock Casino, which is also owned by Tesuque Pueblo.

Demographics

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 909 people, 455 households, and 249 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 130.6 people per square mile (50.4/km²). There were 541 housing units at an average density of 77.7 per square mile (30.0/km²). The racial makeup of the CDP was 75.25% White, 0.44% African American, 0.44% Native American, 0.77% Asian, 18.37% from other races, and 4.73% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 35.64% of the population.

There were 455 households out of which 16.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.5% were married couples living together, 8.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.1% were non-families. 38.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.00 and the average family size was 2.61.

In the CDP, the population was spread out with 14.7% under the age of 18, 4.7% from 18 to 24, 23.8% from 25 to 44, 41.3% from 45 to 64, and 15.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 48 years. For every 100 females there were 89.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.6 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $36,029, and the median income for a family was $80,043. Males had a median income of $43,833 versus $42,650 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $52,473. About 7.3% of families and 12.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including none of those under age 18 and 29.5% of those age 65 or over.

Notable people

Carlene Carter, singer and songwriter.

Lynne and Dennis Comeau, shoe designers.[4]

Howie Epstein, musician.

Ali MacGraw, actress and model.

Armistead Maupin, author who bought the Comeau estate.

Cormac McCarthy, author.

Anthony Michaels-Moore, opera singer.[5]

Eliot Porter, nature photographer who lived in Tesuque from 1946 until his death in 1990.

Michael Tobias, author.

Carol Jean Vigil, New Mexico's first female Native American state court judge.

Cultural references[edit]

Tesuque is mentioned in Willa Cather's 1927 novel Death Comes for the Archbishop, Book Nine Chapter 1.

There is a passing mention of Tesuque in chapter 6 of the 1932 novel Brave New World by Aldous Huxley.

Tesuque is also mentioned in the 1966 novel The Last Gentleman by Walker Percy.

Michael Tobias' 2005 novel, The Adventures of Marigold, is set in Tesuque.

In the final episode of the crime drama series Breaking Bad, the characters Elliott and Gretchen Schwartz live in a new mansion in Tesuque.

In the penultimate episode of the second season of the animated comedy drama series BoJack Horseman, BoJack visits Charlotte Moore who lives in Tesuque in a feeble attempt to rekindle an old romance with her.

Some background on Pueblo Pottery Making

“Pueblo pottery is made using a coiled technique that came into northern Arizona and New Mexico from the south, some 1500 years ago. In the four-corners region of the US, nineteen pueblos and villages have historically produced pottery. Although each of these pueblos use similar traditional methods of coiling, shaping, finishing and firing, the pottery from each is distinctive. Various clay's gathered from each pueblo’s local sources produce pottery colors that range from buff to earthy yellows, oranges, and reds, as well as black. Fired pots are sometimes left plain and other times decorated—most frequently with paint and occasionally with applique. Painted designs vary from pueblo to pueblo, yet share an ancient iconography based on abstract representations of clouds, rain, feathers, birds, plants, animals and other natural world features.

Tempering materials and paints, also from natural sources, contribute further to the distinctiveness of each pueblo’s pottery. Some paints are derived from plants, others from minerals. Before firing, potters in some pueblos apply a light colored slip to their pottery, which creates a bright background for painted designs or simply a lighter color plain ware vessel. Designs are painted on before firing, traditionally with a brush fashioned from yucca fiber.

Different combinations of paint color, clay color, and slips are characteristic of different pueblos. Among them are black on cream, black on buff, black on red, dark brown and dark red on white (as found in Zuni pottery), matte red on red, and poly chrome—a number of natural colors on one vessel (most typically associated with Hopi). Pueblo potters also produce un decorated polished black ware, black on black ware, and carved red and carved black wares.

Making pueblo pottery is a time-consuming effort that includes gathering and preparing the clay, building and shaping the coiled pot, gathering plants to make the colored dyes, constructing yucca brushes, and, often, making a clay slip. While some Pueblo artists fire in kilns, most still fire in the traditional way in an outside fire pit, covering their vessels with large potsherds and dried sheep dung. Pottery is left to bake for many hours, producing a high-fired result.

Today, Pueblo potters continue to honor this centuries-old tradition of hand-coiled pottery production, yet value the need for contemporary artistic expression as well. They continue to improve their style, methods and designs, often combining traditional and contemporary techniques to create striking new works of art.” (Source: Museum of Northern Arizona)

Related Products

Sold out

Sold out